Us

Most people I've talked to seem satisfied that what happened in New Orleans was either the fault of President Bush, or the Federal Government, or the State Government, or city and local government. Already, most of what I hear is one or the other -- New Orleans' demise was due to the failure of our institutions, by various measures. If that's the verdict -- that what happened will be pinned squarely on institutional bureaucracy of one branch or another, without looking at ourselves -- then we're in deep trouble.

David Brooks wrote an interesting commentary this week in the New York Times, regarding Americans' disenchantment with the institutions that are supposed to serve them:

...there is a loss of confidence in institutions. In case after case there has been a failure of administration, of sheer competence. Hence, polls show a widespread feeling the country is headed in the wrong direction.Brooks' essay infers that the institutions we have lost faith in are largely political. But he leaves out the most important institution, core to the human experience -- one that is so basic that it isn't considered an institution, per se: Community.

Katrina means that the political culture, already sour and bloody-minded in many quarters, will shift. There will be a reaction. There will be more impatience for something new. There is going to be some sort of big bang as people respond to the cumulative blows of bad events and try to fundamentally change the way things are.

...We're not really at a tipping point as much as a bursting point. People are mad as hell, unwilling to take it anymore.

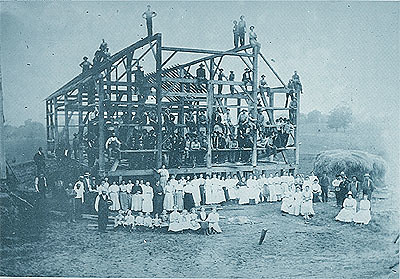

Communities aren't elected at the polls. They aren't created by city planners, or run by unseen bureaucrats. Communities are composed of people, each committed to each others' welfare and by extension, their own. Strong communities are comprised of people with different talents and strengths whose bonds of trust amplify their durability in a dangerous world. Communities share a common survival interest, among other things.

We moved to a small town three years ago on the outskirts of the Bay Area. I remember the day we moved in from San Francisco. Our big yellow Ryder truck was parked in front of our empty bungalow. Neighbors that we didn't know yet came over and offered to help us. At one point during the move there were kids playing in our house while my wife and I were chatting with the people next door. Having just moved from the city, I remember thinking how the neighbors' friendly helpfulness was completely foreign to me. Three years on, we are now surrounded by friends, and a strong network of trust between ourselves and our community here in the hills. Our communal bonds make us safer in the process, aside from the social niceties of wine parties and late night summer patio chats. We're here for each other -- and while our community has yet to face its Katrina, the indications are that we'll be here for each other when it matters most.

The lake formerly known as New Orleans turns out to be an equal opportunity finger pointer. As near as I can tell, New Orleans' demise represents a tragic, catastrophic failure of not only governmental institutions -- be them Federal, state or city -- but in some cases, communal failures as well. And we shouldn't be smug and think communal failure is limited to New Orleans. It could happen anywhere.

We can all be as dissatisfied as we like with the institutions that fail us. But if the buck stops at the President's desk on one end of the accountability scale, surely it must start in our own homes and communities on the other end. We're accountable too. We're in charge of our immediate safety and not leaving it entirely to institutions. All of us are responsible.

Ask yourself if you are prepared for a disaster right now. Do you have enough water or calories stored in your basement to survive a calamity? Most of us don't. We figure that we'll get rescued by one of those institutions we feel so bitter towards. I've been guilty of this, until a few weeks ago, when all the nuclear terror stories motivated me to take some basic precautions.

Both political parties have spent years and billions of dollars on institutional solutions for citizen survival in catastrophic circumstances. Surely, things can be vastly improved on that scale, and responsibility lies at the feet of our public institutions. But we should also assume some accountability, too. Our basic instinct for survival is not an institutional matter. It's personal. And it's communal. In that respect, we're in charge. It's up to us, whether we believe it or not.

I have been shaken by New Orleans and its deeper implications. It leaves me wondering if our sense of community is ebbing in the face of modernity. New Orleans is undoubtedly one of this country's richest cultural gems. Until Katrina, I assumed that culture and community were largely synonymous, and symbiotic. Surely there were strong communities within New Orleans and many stories of heroism will emerge from the receding waves. There already are great stories of heroism, like the medical clinic set up in a French Quarter bar. But the breakdown of communities was also very apparent and cannot be ignored. Along with multilevel governmental derelictions, something fundamental didn't work in New Orleans -- something that goes far beyond political institutions and our disenchantment with them.

We live in an era where networked communities are on the rise. But there are logical limits to sharing values with people who you don't rub elbows with, who are far-flung and offline in the event of catastrophe. Whether we know it or not, we're reliant on our communities who are there in a pinch, in close proximity. Sometimes it's to borrow a cup of sugar. Other times it's to have the neighbor watch your kid so you can deal with an emergency. And sometimes the community is essential for dealing with outright catastrophe.

Our modern culture rewards buying houses with tall fences that keep communities disjointed. It rewards big screen TVs and TiVo to be entertained on command. It rewards anonymous shopping at Wal-Mart, checking out foreign merchandise from an anonymous cashier. Our modern culture rewards walking around with an iPod, shutting out the people around us. It uses art, cuisine and historical cultures as backdrops for tourist brochures. Our modern culture rewards spending most of our time alone, even when we're on the phone, chatting on the Internet, or playing networked video games. It rewards a group of teenage girls I saw the other day at a restaurant booth: four girls, all of them on cell phones talking to someone else, while eating their burgers. Alone together.

Over the years I have become suspicious of what we are building in place of traditional communities. We hear the word 'community' a lot, especially in buzz-terms of social networking. But I think a simple definition of a community is that it is a collection of trusted people you can rely on in whatever life throws at you, no matter how bad. And they rely upon you too, regardless of your 'culture.' It's an old concept that is fraying in the face of modernity's demand that we socialize virtually, even though so many essential bonds are severed in the process.

I heard the phrase today, 'social fabric.' I thought about fabric, and how it is composed of weaves -- interlacing strands that create cloth that is strong, durable and flexible. By themselves, the strands are weak and nearly inconsequential. Seeing the mask fall off of one of America's great cities has me wondering if what we have now is more 'social veneer' -- a smooth, glossy, colorful cultural skin that might rest on stressed, weakening communities. Mr. Brooks pointed out that Americans are losing faith in institutions. Does that include the concept of community? Have we given up on each other too?

I watched a video of two New Orleans policemen helping themselves to shoes at a looted Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart is an institution too -- a commercial one. I suppose we might assume that the looters have lost faith in that institution as well. Maybe if we were still buying all our stuff from Ike Godsey at the general store, looters would vanish out of a sense of communal responsibility. Clearly, some of the looting was a matter of survival. Much of it was not.

I've learned that no matter how rich a culture's heritage might be, it's not synonymous with a robust, responsible, interdependent community of self-reliant individuals. And I'm not making a smug observance of New Orleans' failings. Since Katrina, I now think communal failure can happen anywhere. If cultural pearls like New Orleans can break down so drastically, nowhere is immune.

Certainly, all levels and branches of government deserve scrutiny in the aftermath of Katrina. There's a war on. The disconnectedness between the instutions that we rely on for safety is deeply troubling in the context of war. Let no stone go unturned. And while we rightfully expect better from all levels of government, we should consider looking in the mirror and at our community. The government might be inept, or just slow-moving, but that doesn't take us off the hook. We should examine the communities that exist in our modern culture. We're driving.

America's greatness -- and humanity's, for that matter -- was never defined by institutions. It was defined by people -- by the bold, the creative, and the loving; by the giving, the adamant and the humorous. By us. If culture has become only a pretty thing that is stripped away from community, it doesn't earn preservation. History is full of rich cultures that didn't survive. If all we have built are museums and amusement parks where culture is just a theme and communities are lifestyle choices, we must find ourselves again. All of us.